Chinese Researchers Develop Flexible Brain Implants Inspired by Kirigami Art

According to the Economic Desk of Webangah News Agency, researchers in China have engineered a new generation of soft, pliable brain implants taking inspiration from the Japanese art of origami, specifically the kirigami variation. This development aims to revolutionize brain-computer interface (BCI) technology by allowing the implant to move fluidly with the brain rather than remaining rigid.

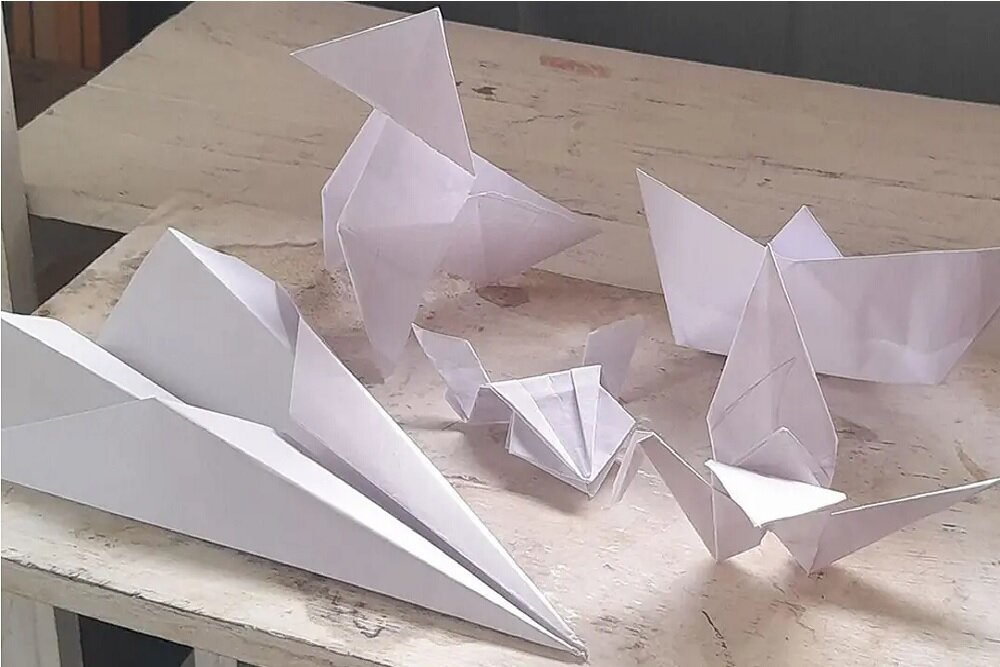

Kirigami, a Japanese art form related to origami, involves making strategic cuts and folds in paper to achieve complex three-dimensional structures. Engineers favor this technique because it allows flat materials to be stretched, bent, and twisted without fracturing as they transition into three dimensions.

Current BCI interfaces, such as those developed by Neuralink, rely on small electrode strands implanted into the brain to capture neural signals. A significant challenge with these rigid systems is that the brain is in constant motion due to heartbeats and respiration. This movement causes traditional BCIs to shift or contract over time, leading to diminished signal quality, potential inflammation, or tissue damage.

Researchers noted in their published paper that developing effective BCIs requires implantable microelectrode arrays capable of communicating with numerous neurons across large spatial and temporal scales. The instability introduced by tissue interaction often results in device migration, which compromises signal fidelity.

Fang Ying, the senior researcher at the Chinese Institute for Brain Research, stated that the team recognized approximately four years ago the real danger of flexible electrodes contracting due to brain movement. This realization prompted them to explore new methodologies to mitigate the risk of electrodes pulling out when one end is fixed within the brain and the other anchored to the skull.

The team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences addressed this issue by transforming the electrode threads of the BCI into a helical structure inspired by ancient Japanese paper-folding techniques, rather than relying on conventional threads. Helices possess the critical ability to stretch and compress, absorbing motion instead of resisting it, thereby reducing mechanical stress on the delicate brain tissue.

Furthermore, this new BCI is situated atop a layer of hydrogel upon implantation. This hydrogel acts as a buffer against brain movement, minimizes friction, and lessens tissue damage during deployment, allowing the electrodes to essentially float over the brain surface rather than rigidly adhering to it.

The experimental results were significant. When tested on macaque monkeys, whose brain structures closely resemble those of humans, the origami-inspired BCI successfully recorded the simultaneous activity of over 700 cortical neurons. The interface effectively covered a substantial brain region, maintained stable signal recordings, and demonstrated considerably less displacement compared to conventional designs.

This stability is paramount, as BCIs are intended for critical applications such as enabling paralyzed patients to control robotic limbs, restoring speech, treating neurological disorders, and potentially enhancing human cognition. If the device can move in sync with the brain, it prevents signal loss, avoids inducing inflammation, and protects tissue, ensuring long-term functionality.

The successful navigation of this mechanical challenge using the kirigami-inspired approach marks a major potential breakthrough for the future of BCI technology. The study detailing these advancements was published in the journal Nature Electronics.